Help Center

Online Resource Center for Information on Birth Injuries.

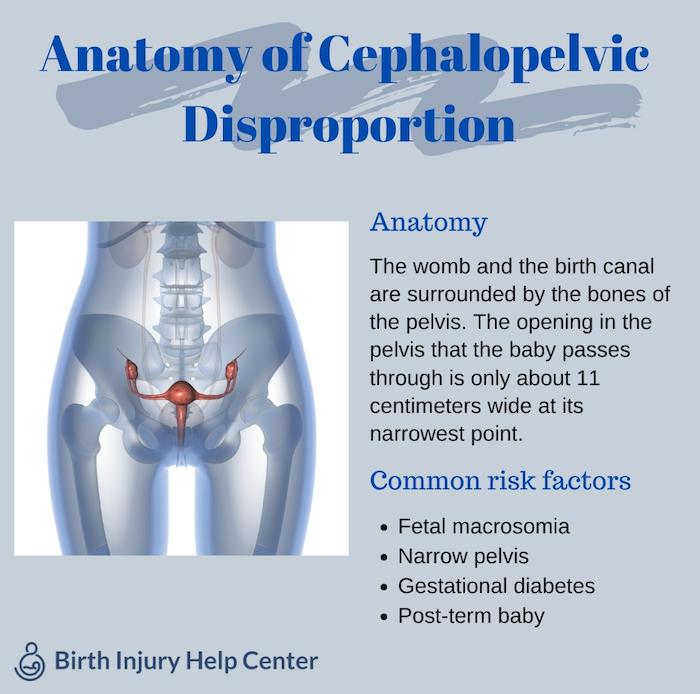

Cephalopelvic disproportion is the full form of CPD which is when a baby’s head is too large to fit through the mother’s pelvis. When a baby is too large, it becomes challenging if not impossible for the baby to be delivered vaginally.

The term is often applied more generally by OB/GYNs as the cause of labors that for whatever reason become obstructed and fail to progress. The safest option once CPD is diagnosed is to perform a c-section. Usually a c-section is planned in advance if doctors know that a baby is extremely large or that there is a complication with the mother, however, CPD is often discovered during labor.

With true CPD, there is a mismatch in size between the mother’s pelvis and the baby’s head. This is either due to the baby being especially large or the mother’s pelvis being especially small.

With true CPD, there is a mismatch in size between the mother’s pelvis and the baby’s head. This is either due to the baby being especially large or the mother’s pelvis being especially small.

The medical term for when the fetus is overly large is fetal macrosomia. Macrosomia is defined as over 8lbs 13 oz. About 10% of pregnancies, and 50% of pregnancies with gestational diabetes, are affected by macrosomia. But how does a baby grow too big to be born vaginally? Babies can be large for a number of reasons, including:

It is also possible for mothers to have small or abnormally shaped pelvises. This occurs because of a prior injury to the pelvis or genetic factors. Adolescents and shorter women are more likely to experience this problem. An injury or malformation of the pelvis can also affect childbirth. The pelvis may be misshapen, have bony growths, or have a bone out of place.

Other risk-factors include polyhydramnios (excess amniotic fluid) and multiparity (having given birth previously, either vaginally or by c-section).

Obstetricians can use radiologic pelvimetry, a type of imaging technology that measures the dimensions of the mother’s pelvis, to predict or confirm CPD. Ultrasounds can be used to estimate the size of the baby’s head. However, studies have found a poor correlation between the use of imaging technologies and labor outcomes.

This is because the bones in the baby’s head are meant to change shape in order to pass through the birth canal. Many petite mothers carrying babies with heads that appear large are still able to successfully deliver vaginally. Additionally, imaging technologies are not as precise as obstetricians would like. They can only estimate the baby’s size, not measure it exactly.

Given these circumstances, doctors do not necessarily schedule a c-section in advance just because a baby looks large or a mother’s pelvis seems small. A c-section may not be indicated unless it is obvious that the baby will be too big for the mother to deliver vaginally or there is some other complication with the pregnancy such as a prior pelvic injury. What this means is that CPD is often diagnosed during labor, not before.

During labor, doctors monitor the position of the baby in the birth canal, uterine contractions, and the dilation of the cervix. When doctors see that the baby is not moving through the birth canal as expected, they may administer a drug such as oxytocin to stimulate labor. If the labor is still slow or if labor becomes completely obstructed, doctors will perform an emergency c-section to deliver the baby. If they don’t promptly perform a c-section, the baby may suffer from oxygen deprivation, which can cause a number of birth injuries, including cerebral palsy.

CPD happens in about 1 out of every 250 births. In otherwise normal pregnancies, babies are macrosomic 10% of the time.

There are several factors that make pregnancies high-risk. The specific risk factors for CPD include gestational diabetes, fetal macrosomia, genetic predisposition, and post-term pregnancies.

Just because a mother experiences CPD in one pregnancy does not mean that she will experience it again in subsequent pregnancies. In a study, more than 65% of women diagnosed with CPD gave birth vaginally to another child. Usually in this situation, mothers can elect to have a c-section or attempt a vaginal delivery.

Doctors may use drugs such as oxytocin that induce labor as a first response to labors that are not progressing normally. Additionally, with conditions such as shoulder dystocia when a baby is stuck, obstetricians may use tools like forceps or vacuum extractors to reposition and guide the baby.

However, with true CPD, the baby has little chance of fitting past the mother’s pelvis. Doctors need to quickly recognize fetal distress and obstructed labor and perform a c-section in order to prevent the baby from being seriously injured. Repeated attempts to deliver vaginally that prolong labor are dangerous.